• What is a function

• Parameters

• Return values

• Scope

• *args and **kwargs

• Lambda, etc.

In this part, we will continue our learning journey and explore new topics (related to functions topic) that developers use on a daily basis. I have planned the below topics for this post:

• Understand the difference between user-defined and built-in functions

• How the math module saves time

• How the pass keyword is useful in planning

• What nested functions are, with practical examples.

As you continue learning, you’ll notice that small improvements in understanding functions make a big difference in how you write Python code.

1. User-Defined vs Built-In Functions

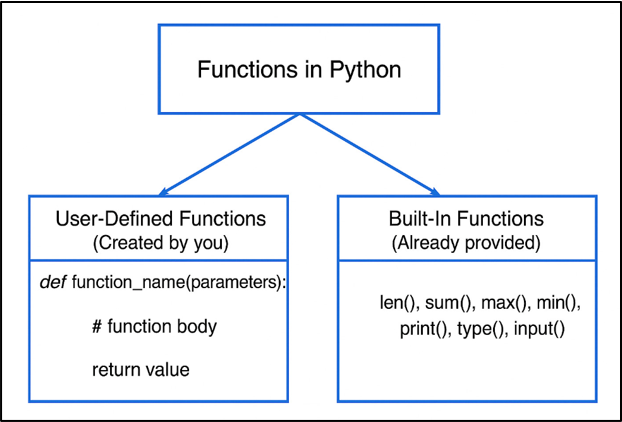

There are two types of functions in Python language, as shown below:

a) User-Defined Functions

b) Built-In Functions

Let us understand both types of functions in a simple way:

a) User -Defined Functions:

A user-defined function is created by you based on your needs.

For example, if you want to perform a particular task (say, addition of two numbers), then you can write a function that performs the addition of two numbers. Since you created this function, then it is called a “User-Defined Function.”

Syntax:

def function_name(parameters):

# function body

return value

Example: User-Defined Function

def sum(a, b):

"""This function takes two numbers (a, b) as input and returns their sum."""

result = a + b

return resultExplanation:

In this example, the function sum(a, b) is created to add two numbers. The triple-quoted line is a docstring, which describes what the function does.

Inside the function, Python adds variables a and b and stores the total in result. Finally, the return statement sends that total back to wherever the function was called.

Most beginners actually understand functions much faster when they see simple examples like this in action.

b) Built-In Functions:

In Python language, a built-in function is already available. You don’t need to write code for it. You can use it instantly.

Some examples of built-in functions are given below:

len(), sum(), max(), min(), print(), type(), and input().

Syntax:

built-in-function(arguments)

Example 1:

numbers = [5, 10, 15, 20]

result = max(numbers)

print(result)

Output:

20

Explanation:

In this example, we first create a list named numbers that stores four values: 5, 10, 15, and 20.

Then we use the max() function, which simply looks through the entire list and picks the biggest number.

The result is stored in the variable result, and when we print it, Python shows 20 on the screen.

Example 2:

a = 50 # Integer

b = "Hello" # String

c = [10, 20, 30] # List

print(type(a))

print(type(b))

print(type(c))

Output:

<class 'int'>

<class 'str'>

<class 'list'>

Explanation:

In this example, three different variables are created: a store a number (50), b stores a piece of text ("Hello"), and c stores a list of values ([10, 20, 30]). When we use the type() function, Python tells us what kind of data each variable hold. So, type(a) shows <class 'int'>, meaning it’s an integer, type(b) shows <class 'str'> for a string, and type(c) shows <class 'list'> for a list.

This helps students understand that Python treats different values differently, and knowing their type makes debugging and writing code easier.

Example 3:

my_list = ["Aman", "Raj", "Raman"]

my_string = "Python"

my_dictionary = {"x": 10, "y": 20}

print(len(my_list))

print(len(my_string))

print(len(my_dictionary))

Output:

3

6

2

Explanation:

In this example, three different data structures are created: a list, a string, and a dictionary. The len() function is then used to check how many items each one contains. When Python runs these lines, it finds 3 items in the list, 6 characters in the string "Python", and 2 key-value pairs in the dictionary.

Overall, the len() function is a simple way to measure the size of any collection in Python. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a list of names, a word, or a dictionary—Python counts what’s inside and returns the number.

You’ll use these built-in functions hundreds of times in real projects without even realizing it.

Difference Between User-Defined vs Built-In Functions:

| User-Defined Functions | Built-In Functions |

| 1. These are written by programmer when they want the program to do a specific task. | 1. These functions are already provided by Python and ready to use. So, there is no need to write any function. |

| 2. These are used when Python doesn’t have a ready-made function for our task. | 2. These are used to save time because they handle common tasks very quickly. |

| 3. You need to write the logic, test it, and make sure it works properly (as per need) | 3. No effort is needed, you only need to call the function and it works. |

| 4. These are highly flexible because you design the function as per your requirement. | 4. These are less flexible, as they have fixed behavior decided by Python developers. |

Why It Matters

a) User-defined functions make your program reusable.

b) Built-in functions provide you shortcuts for common tasks.

c) It is always good to use built-in functions whenever possible.

d) If you know the difference between these two, then it helps you write clean and fast code.

2. import math:

In Python, math is a built-in module that has built-in functions.

One doesn’t need to write these functions manually. You can use these functions directly in your program (as per need).

A few function names are:

• sqrt()

• factorial()

• pow()

• log()

• ceil()

• floor()

• sin()

• cos()

This module is used heavily in AI, ML, and engineering-specific tasks and makes your work faster and more accurate.

Example 1: Using Common Math Functions

import math

print(math.sqrt(16)) # Square root

print(math.factorial(5)) # Factorial

print(math.pow(3, 2)) # 2^3

print(math.log(10)) # Natural log (base e)

print(math.ceil(4.1)) # Round up

print(math.floor(4.9)) # Round down

print(math.pi) # Value of pi

Output:

4.0

120

9.0

2.302585092994046

5

4

3.141592653589793

Explanation:

In this example, we import Python’s math module and use some of its most common functions. When we call math.sqrt(16), it calculates the square root and gives 4.0. The math.factorial(5) line finds the product of numbers from 1 to 5, which becomes 120. Then math.pow(3, 2) raises 3 to the power of 2 and returns 9.0, followed by math.log(10) which prints the natural logarithm of 10 as 2.302585092994046.

After that, math.ceil(4.1) rounds the number upward to 5, and math.floor(4.9) rounds downward to 4. Finally, math.pi simply prints the value of π, which is 3.141592653589793.

Please note that each of these functions saves time because you don’t have to write the logic yourself, the math module already knows how to do it.

Example 2: Trigonometry & Radians

import math

angle_deg = 45

angle_rad = math.radians(angle_deg) # Convert to radians

print(math.sin(angle_rad)) # Sine value

print(math.cos(angle_rad)) # Cosine value

print(math.tan(angle_rad)) # Tangent value

Output:

0.7071067811865476

0.7071067811865476

0.9999999999999999

Explanation:

In this example, we first take an angle of 45 degrees and convert it into radians using math.radians(), because Python’s trigonometric functions always work in radians.

After that, we pass it to math.sin(), math.cos(), and math.tan()functions to get their respective values. That’s why the output shows the sine and cosine both as 0.7071067811865476, and the tangent very close to 1.0, which is what we expect for a 45-degree angle.

All these output values show how Python language handles the trigonometric calculations internally.

Important Points:

a) Math module functions are optimised in C language, so they run faster than manually writing formulas.

b) Math module comes with built-in with Python language, so you don’t need to install it.

c) In AI / ML projects, math functions like log, sqrt, ceil, and floor are used in data cleaning and preprocessing phase.

d) In machine learning datasets, two functions math.isfinite() and math.isnan() are used (frequently) to check for invalid values like NaN or infinity.

e) It makes your code short and less error-prone.

3. The pass Keyword:

In some situations, when you start writing a program, you realize that you need to write a function but you haven’t decided what code will go inside it. Then you need a placeholder to avoid an error.

The pass keyword acts like writing a “Coming Soon” sign in an empty function.

The Problem:

def process_data():

# Python doesn’t allow an empty function body

# This code will crash

The Solution (Using pass):

Syntax:

def function_name(parameters):

pass

Example:

def generate_report():

passExplanation:

In this example, the function generate_report() is created but it contains only the keyword pass, which simply tells Python language, “I will fill this later, please don’t give an error.”

It’s like keeping an empty placeholder when you’re planning your code structure.

When you run this program, nothing is printed on the screen because the function has no real body yet.

Real-World Applications:

a) In AI and ML projects, developers create empty functions first while building ML pipelines:

• load_data()

• clean_data()

• train_model()

• evaluate_model()

These empty functions are filled later as the project grows.

b) When you work in a large team, first you create only function names and then assign their implementation to your team members. In this way, everyone in the team remains aligned with the structure.

Why pass Is Important

a) In large projects, you can make planning easily.

b) It is very useful for dividing tasks in a large team.

c) It helps to prevent errors during development.

d) It helps in designing code before writing real logic.

4. Nested Functions:

It is a function defined inside another function.

Please note that an inner function is always created and used within the outer function. It makes your logic more organized and secure.

Once you start grouping related tasks inside one main function, your code immediately feels cleaner, more readable, and easier to manage.

Example: Structure of a Nested Function

def outer():

print("You are inside the outer function")

def inner():

print("You are inside the inner function")

inner() # calling the inner function

outer() # calling the outer function

Output:

You are inside the outer function

You are inside the inner function

Explanation:

In this example, the function outer() starts its body right after the colon, and everything that stays indented under it is part of that body. This includes the first print statement, the full definition of inner(), and the line where inner()function is called. The body ends the moment the indentation comes back to the left side.

When the program finally reaches outer()and calls the outer()function , Python steps inside and prints the first message.

After that, it sees the call to inner(), moves into the inner function, and prints the second message. That’s why the output appears exactly in following order:

• You are inside the outer function

• You are inside the inner function.

Important Points:

a) Nested functions act like a private function. So only the outer function knows about it. Hence, no one from outside can access or modify the inner logic.

b) It keeps your code organized because you keep small functions inside one bigger function.

c) It helps you group related tasks together inside one main /outer function, as the inner function handles a small job.

Example:

def outer_task():

# define main work here

def inner_task1():

# define first task here

pass

def inner_task2():

# define second task here

pass

inner_task1()

inner_task2()Explanation:

In this example, the body of outer_task() begins right after the colon, and everything indented under it belongs to this function. That includes the definitions of inner_task1() and inner_task2(), as well as the two lines that call them. The body ends as soon as the indentation moves back to the left side.

However, the outer function is only defined, not executed. Since the program never calls outer_task(), Python does not step inside it. And because the calls to inner_task1() and inner_task2() sit inside the outer function’s body, they also never run. They remain inactive even though they are written in the code.

The above example show that how related tasks can be grouped inside a main or outer function function. Each inner function is ready to handle a small job, but none of them will actually execute unless the outer function itself is called first.

With this post (Python Functions: Part 3), you now clearly understand the discussed topics, which will help you write clean, reusable and well-structured code in real projects.

If any of these topics felt new today, don’t worry- these are exactly the things developers pick up gradually with practice.

Learn more about Functions in our “Python Decorators Explained" chapter.