1. What is a Generator?

Prerequisite: To understand Python generators clearly, you should be comfortable with Python Functions Basics and Python For Loop.

A generator is a special function that returns a sequence of values one at a time, pausing between each value.

Generators help us achieve following major benefits:

a) Memory Efficient

Generators produce values one at a time. Thus, they save a huge amount of memory because they don’t store the complete data set.b) Handle Large Data Efficiently

They don’t run all data in memory. So, they run faster, especially in scenarios where you need to deal with millions of records.c) Good for Streaming & Infinite Data

Generators don’t freeze your system; rather, they continue to produce values forever (like log files and real-time APIs).d) Perfect for Pipelines

They are ideal for ML pipelines, ETL workflows, and chained operations because they allow step-by-step processing.2. How yield Works?

In order to understand generators, one must understand the yield statement.

Once Python sees a yield statement inside a function, it does not behave like a normal Python function.

That function doesn’t return everything at once. Instead, that function becomes a step-by-step data producer.

Let me explain how yield actually works in simple words:

a) Once the yield statement runs, it only sends a single value back to the caller function.

b) After that, it immediately pauses the execution of the rest of the code, and the function stops there.

c) It remembers all its variables and position so that during pause time, nothing is lost.

d) When the function starts executing again, it resumes exactly where it stopped once it is called again.

From my real project experience:

I clearly understood the power of yield when I was working on a production data pipeline where loading the full dataset into memory was not possible.

At that point, yield was not a language feature - it was the only way to keep the system stable.

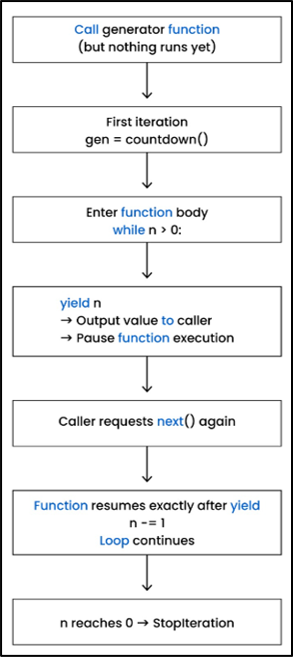

How a Python Generator Executes (Step-by-Step)

This diagram shows the full execution lifecycle of a Python generator.

Notice that calling the generator function does not execute any code until next() is invoked. Each yield sends a value to the caller and pauses execution until the next request.

3. Basic Generator Example

Let us try to understand how a generator works by taking a very simple example.

def count_x(n):

while n > 0:

yield n

n -= 1

# create generator

gen = count_x(5)

print(next(gen))

print(next(gen))5

4

Explanation:

In this example, first we have defined a function named count_x() which takes a number n. This function contains a yield statement, so it becomes a generator function (not a normal function).

Next, we have defined a loop that will continue to run until n is greater than 0.

When Python runs the yield statement, it performs the following tasks:

a) Returns the value of n to the caller

b) Immediately pauses the function and remembers the value of n

c) Next time next() is called, execution starts from this line (not from the start)

The next statement n -= 1 subtracts 1 from n.

This is how the while loop works.

After that, the following statement is executed:

gen = count_x(5)

Please remember that the above line has created a generator object, and gen now contains the reference of the generator object. The function count_x() is not executed yet at this point.

The function will start running only when we call next().

After that, the next line is:

print(next(gen))

This is the first time next() is called. With this call, execution starts with n = 5, and yield returns 5 and immediately pauses execution.

The last line is:

print(next(gen))

This is the second next() call.

This time, the function starts execution exactly at the point where it paused last time. It continues after the yield 5 statement, and now the value of n becomes 4. Again, it checks the while loop (n > 0) and runs the yield 4 statement.

At this time, it returns 4 and pauses again.

Hence, the final output is:

5

4

Why this example matters in real life:

I often use this exact countdown-style generator pattern when validating batch sizes, retry attempts, or paginated records. It helps control execution flow without keeping counters or states outside the function.

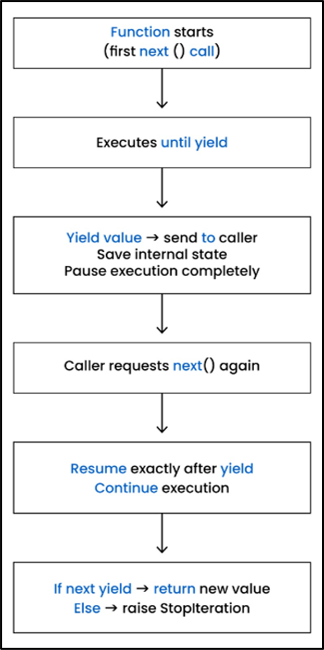

Python Generator Execution Using yield and next()

This flow focuses specifically on how yield and next() interact.

The generator executes only until it reaches a yield, saves its internal state, and resumes exactly from that point when next() is called again.

Modified Example Using for Loop

def count_x(n):

while n > 0:

yield n

n -= 1

for x in count_x(5):

print(x)

Output:

5

4

3

2

1

for Loop (in Simple Words)

count_x() is the same generator function (as we discussed before).

Let’s understand the next part of the code (shown in the above example) — the for loop — in simple words.

Always remember that a for loop automatically calls next() on the generator again and again.

You never see next(), but it is secretly called by Python.

Let me show you how Python runs the for loop internally.

The code shown below:

for x in count_x(5):

print(x)is actually converted/replaced by the following code:

gen = count_x(5)

while True:

x = next(gen)

print(x)Explanation:

The statement gen = count_x(5) creates the generator object.

Each time the statement next(gen) is executed, the generator function returns the next value and pauses.

Once the value of n becomes 0, the while loop stops, and the generator doesn’t have more values. At that point, a StopIteration exception is raised internally, which simply means that the generator is finished.

4. Real-World Example: Streaming a Log File

def read_logs(path):

with open(path) as f:

for line in f:

yield line.rstrip("\n")Explanation:

In the above example, read_logs() is a generator function which reads a log file, but only one line at a time.

In the next line, the file is opened safely and is also closed automatically afterward.

Please note that a file object f is created, which is used to read line-by-line data from the file.

In the last line, the yield statement returns one cleaned line at a time (and also removes the ending newline).

In short, the above generator function pauses after each line and continues when the next line is requested.

This is very useful when you have to read large log files in an efficient way.

Production insight:

In one of my projects, we were processing multi-GB log files generated every day. Using a list-based approach caused memory spikes and frequent crashes. Switching to a generator-based log reader stabilized the system and reduced memory usage drastically.

5. Production-Level Pattern: Paginated API Streaming

In past years, I got a chance to work with many APIs that send data in multiple pages (rather than sending all data in a single shot). This approach protects the server from crashing as well.

In this, we implemented paginated responses, where the server only sends a few records per page. This approach reduces load and keeps the server stable.

This approach provides multiple benefits:

• Avoids huge data transfers

• Reduces the load on server memory

• Helps to avoid request timeouts

• Helpful in high-traffic scenarios

Example:

import requests

def fetch_users():

url = "https://api.example.com/users?page=1"

while url:

res = requests.get(url).json()

for user in res["results"]:

yield user

url = res.get("next")Explanation:

import requests imports the requests module, which helps a program to talk to APIs through HTTP calls.

The function fetch_users() is used to fetch users one page at a time. This is also a generator, as it contains a yield statement.

The variable url stores the URL of page 1.

The while url: statement tells Python that as long as there is a valid URL, keep fetching the data.

requests.get(url).json() sends a GET request to the URL and converts the response into a Python dictionary using .json().

The API response contains multiple users inside "results". With the help of yield, only one user is returned at a time, execution is paused, and it resumes once the next user is requested.

url = res.get("next") is used to fetch the URL of the next page inside "next".

If the next page URL exists, the loop continues. Otherwise, the loop stops, which means there are no more pages.

Real project context:

I have worked with APIs that returned millions of records but limited responses to a few hundred items per page. Without generators, handling such APIs would either fail or cause timeouts. Using a generator to stream paginated responses helped us process data reliably under high traffic.

6. Generator Expressions

Based on my experience, it is very important to understand the difference between list comprehensions and generator expressions.

It helps in writing efficient code in the Python language, especially in scenarios where you are working with large datasets or memory-heavy applications.

Let us now understand each in simple words.

a) List Comprehension:

nums = [x*2 for x in range(1_000_000)]

1. [] tells Python to create a list.

It tells Python to create a list of 1,000,000 numbers where each number is x*2 and x starts from 0 to 999,999.

After execution, nums contains 1,000,000 elements like:

[0, 2, 4, 6, 8, ..., 1,999,998]

Generator Expression:

nums = (x * 2 for x in range(1_000_000))

At first, it looks the same as the last example (list comprehension), but it behaves differently in Python.

It tells Python to create a generator that will give double numbers from 0 to 1,999,998 only when requested, and also, it won’t store them all in memory.

() tells Python to create a generator.

Comparison Table:

| Feature | List Comprehension | Generator Comprehension |

| 1. Memory usage | It needs high memory, as it stores all elements inside RAM. | It needs very low memory, as it stores only one value at a time. |

| 2. Speed | It works faster with small datasets. | It works faster even with large datasets. |

| 3.Execution Mode | It computes everything immediately. | It computes values only when they are needed. |

| 4.Lifetime | It will stay in memory until you delete it. | It is deleted automatically once values are consumed. |

| 5.Indexing | It supports indexing like num[2]. | It doesn’t support indexing like num[2]; it will raise an error. |

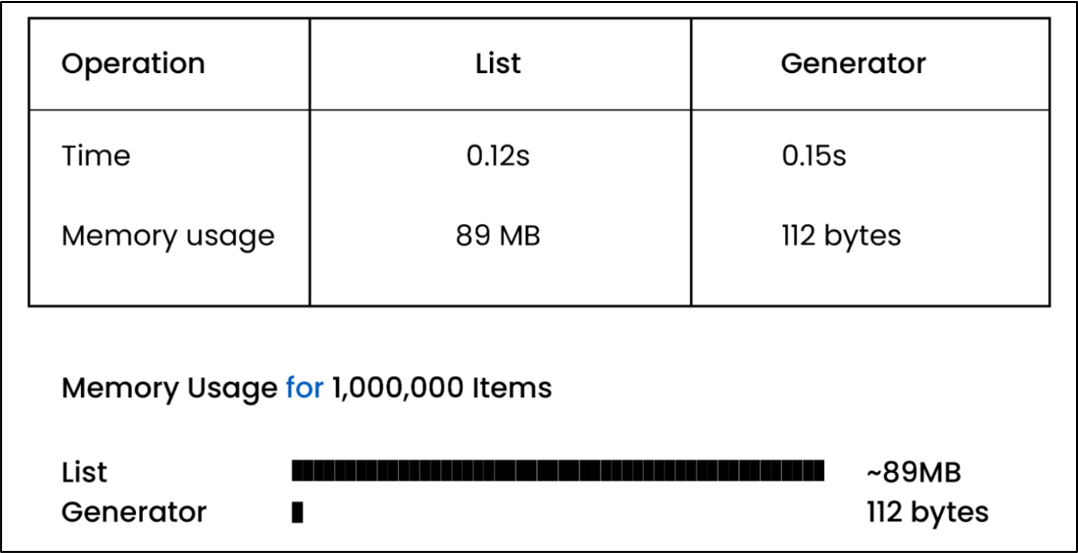

7. Performance Benchmarks (Speed & Memory)

If you want to understand the complete difference between list comprehension and generator expression, then it is very crucial to compare their real performance.

The below-given code compares how fast and how much memory these two (list comprehension and generator expression) use when processing 1,000,000 items.

Example: Benchmark Code

import timeit

import sys

list_time = timeit.timeit("[x*2 for x in range(1_000_000)]", number=1)

gen_time = timeit.timeit("(x*2 for x in range(1_000_000))", number=1)

# memory usage

lst = [x for x in range(1_000_000)]

gen = (x for x in range(1_000_000))

print("List time:", list_time)

print("Generator time:", gen_time)

print("List memory:", sys.getsizeof(lst))

print("Generator memory:", sys.getsizeof(gen))Output:

List time: 0.12s

Generator time: 0.15s

List memory: 89 MB

Generator memory: 112 bytes

Explanation:

import timeit

It loads Python’s in-built stopwatch module. It tells how long a piece of code takes to run.

import sys

sys is Python’s toolbox, and it is used to check how much memory is consumed by an object.

The third line of code runs the list comprehension once and tells how many seconds it takes to run and stores it in a variable list_time.

Similarly, variable gen_time stores how fast Python creates a generator expression.

In the next two lines (7 and 8), we print list time and generator time values.

In the last two lines (9 and 10), we print the size of how much memory is occupied by lst and gen objects respectively with the help of getsizeof().

Note:

getsizeof() is a method inside the sys module. This is used to know how much memory is taken by a Python object.

8. Memory Comparison

I have given a memory comparison, below visual, to show clearly why generators are far more efficient for large datasets.

As you can see, for 1,000,000 items, a list object consumes 89 MB memory.

On the other side, for the same amount of data, a generator consumes only 112 bytes of memory, as it does not store anything and produces only one value at a time.

That is why generators are mostly used for huge datasets in the following scenarios when:

• You need to work with huge datasets

• You are working with streaming pipelines

• You have memory-sensitive applications

In real systems, basic yield is rarely enough. I encountered scenarios where generators had to accept external signals, handle failures, or clean up resources safely. That is where advanced patterns like send(), throw(), and close() become essential.

9. Advanced Generators Patterns

If one wants to learn advanced generator patterns, then you need to go beyond basic yield.

Advanced patterns like send(), yield from, close(), and throw() help you in the following ways:

• Make your code clean

• Connect multiple generators together

• Allow two-way communication with a running generator

Hence, these advanced techniques will help you in real projects in the following scenarios like when:

• You are streaming data

• You are building pipelines

• You want to avoid heavy memory usage

Based on my experience, I can confidently say that once you learn about these advanced patterns, it will make your generators:

• More powerful

• More flexible

• Production-ready

9.1 What is send() in Generators?

Normally, a generator gives values outward using yield.

But with send(), one can also send a value back inside the generator at the exact point where it paused.

Example:

def demo():

x = yield "Hello"

print("Take", x)

g = demo()

next(g)

g.send("Care")Take Care

Explanation:

In this example, first we have defined a generator function named demo().

The statement g = demo() creates the generator function object, and g contains the reference to that object.

In the next statement, when you call next(g), the generator function demo() runs until yield and returns a string "Hello". At this point, the generator is paused, and no code is executed after the yield statement.

In the last line of code, when you call g.send("Care"), the word "Care" goes inside the generator function and is stored in the variable x.

After that, the generator starts its execution and prints the following output:

Take Care

Key Rule to Remember:

If you want to use send(), then first you should start the generator using next().

Otherwise, Python does not know where it needs to send the value.

9.2 Using yield from (Chaining Generators)

It yields all values from another iterable (like a list, tuple, or another generator) one by one.

Let us explain it with a simple example.

def show_x():

yield from ["Pen", "Pencil"]

yield "Eraser"

print(list(show_x()))["Pen", "Pencil", "Eraser"]

Explanation:

In the above example, first we have defined a generator function.

In the second line, there is a yield from statement which tells Python:

“Take each item from this list and yield it one by one.”

In the third line, the generator returns one more value "Eraser".

The last line is a print() statement. When we write show_x(), Python creates a generator object automatically.

Please note that we didn’t store the generator object in a variable like:

g = show_x()

But the list() function receives that generator object and pulls values from the generator until the generator is finished.

In this case, you don’t need to call next() manually because list() calls next() in the background to pull values from the generator function.

9.3 Closing a Generator

Normally, a generator keeps producing until it produces all values.

But in some cases, you want to stop the generator in the middle so that it can no longer produce values.

Please note that once you close the generator, it raises an exception called “ GeneratorExit”, so the generator can finish the execution safely.

def numbers():

try:

yield 10

yield 20

yield 30

finally:

print("Generator is closing, cleaning up!")

g = numbers()

print(next(g))

print(next(g))

g.close()Output:

10

20

Generator is closing, cleaning up!

Explanation:

In the above example, first we have defined a generator numbers().

After that, there is a try block that contains 3 yield statements.

Next, there is a finally block that would be executed if the generator is stopped early. In real projects, it contains the cleanup code.

In the next line, Python creates a generator object and stores the generator object reference in a variable g.

g = numbers()

In the next statement, when we call next(g), then the generator function runs, and when it reaches the yield 10 statement, it pauses the execution and returns 10.

print(next(g))

In the second print statement, when we call the next(g) function, then it starts execution where it stopped earlier and reaches yield 20. It pauses and returns 20.

print(next(g))

In the last line, when Python calls close(), then it runs the code inside the finally block and stops the generator and prints the following line:

Generator is closing, cleaning up!

Please note that once you have closed a generator, you can’t use it again.

Real-World Applications:

In my real project experience, one can use close() in the following scenarios when:

a) Reading large log files

You are reading large log files, and you want to stop the generator early.

b) Streaming pages from an API

You are streaming pages from an API, and you only need the first 2–3 pages, so you can close the generator in the middle.

c) Database or API connections

If a generator is reading data from a database or API, while running, it keeps the connection open.

If you close the generator, then it immediately shuts the connection and saves resources.

9.4 Raising Exceptions Into a Generator (throw())

Normally, send() is used to send values into a generator.

In some scenarios, the situation is totally different. For example, an error is detected in outside code (due to API failure or bad data), and we want the generator itself to react to that error.

In such cases, an exception is sent into a generator using throw(). This exception is injected at the point where the generator was paused at yield.

If the generator function has a try-except block, then it catches the exception, cleans up or retries, and continues just like a normal function.

Example:

def demo():

try:

yield 10

except ValueError:

print("ValueError is caught!")

yield 20

g = demo()

print(next(g))

g.throw(ValueError)

print(next(g))Output:

10

ValueError is caught!

20

Explanation:

In the above example, a generator function is created using the g = demo() statement.

After that, the generator is started using the first call to next(g), and it runs the yield statement (inside the try block), returns 10, and pauses.

After that, an exception is injected exactly at the paused yield point using:

g.throw(ValueError)

This exception is caught by the except ValueError block and prints:

ValueError is caught!

Once the error is handled, the generator continues execution and reaches yield 20.

After that, Python calls next(g) and returns 20.

9.5 itertools Integration

itertools is a module that gives you ready-made generator tools.

These tools help you work with sequences without creating large lists in memory.

Why Use itertools with Generators?

The itertools module gives you pre-built generator tools/functions that help you:

• Save memory

• Improve readability

• Reduce code

• Work with for loops and other generators

a) itertools.chain()

It joins lists together without actually merging them into a new list.

The chain() function walks through the first list, after that it continues to walk through the second list and produces values only one at a time.

Example: Combine Two Lists Using chain()

from itertools import chain

for x in chain([1, 2], [3, 4]):

print(x)Output:

1

2

3

4

Explanation:

In the above example, the chain() function returns a generator.

Please note that it doesn’t create any list. For each iteration, it takes one number at a time from the generator and prints it.

So, the for loop stops working when there is no value left inside the generator.

Because there are only 4 values inside the generator, that is why the loop runs 4 times and produces output as shown below:

1

2

3

4

b) itertools.count()

count() is a function inside the itertools module.

It is an infinite generator that can generate numbers starting from a given number without ending until you stop it in a manual way.

Example:

from itertools import count

for n in count(10):

print(n)

if n == 14:

breakOutput:

10

11

12

13

14

Explanation:

In the above example, first we import the count generator from the itertools module.

In the next line, for n in count(10):, first a count() generator is created, and it generates numbers one by one, starting from 10.

After that, the number is printed using the statement print(n).

In the next line, we have defined a condition using the if statement. If the value of n is equal to 14, then it executes the break statement, and control jumps out of the loop immediately.

Hence, the above program prints values starting from 10 to number 14.

10. Why Generators Matter

a) Almost Zero Memory

As generators produce only one value at a time, for example, if you have millions of items, even then your memory usage will be very low.

b) Scalable

Generators work efficiently with large files, logs, or streams because they don’t load all data at once. Due to this, your program doesn’t crash and it runs fast.

c) Production Systems (ETL, Logs, APIs)

In real projects, generators are mostly used for:

• Streaming data from APIs

• Reading log files to process each line as it comes

• ETL pipelines to move data in small chunks

d) Infinite Items

In a list, you can’t store an infinite number of items, but a generator function keeps producing values infinitely when you ask, so there is no memory wastage.

11. Five Common Mistakes

In my experience, I have seen freshers do the following mistakes continuously, so please avoid the following mistakes:

a) No Index

Generators don’t support indexing like gen[0] or gen[1]. They can produce values only in order and one value at a time.

b) Mixed Signals

Normally, freshers (0–2 years experience) write a yield statement and after that they also write a return value. They don’t realize that return is only used to finish the generator cleanly.

c) No Output

Freshers expect that generators will print values automatically, but they can only produce values. If you want to see the output, then you should use next() or loop through them.

d) Over Nesting

Some people like to have deeply nested generators (yield inside yield inside yield), and this type of over-nesting makes debugging very hard. My advice is to keep generators small and chain them wisely.

e) Closing Ignored

Many freshers and even experienced developers sometimes forget to call close() to free the resources. It keeps resources open longer than needed, and sometimes it causes memory leaks as well.

12. FAQs on Python Generators

1. What is a generator in Python?

It is a function that returns values one by one using yield. Also, generators are memory-efficient and can handle large data efficiently.

2. How is a generator different from a list?

Normally, a list stores all items in memory, but a generator produces items one by one, and this way it saves a huge amount of memory.

3. Are generators faster than lists?

Lists are faster if you have a small-sized dataset. On the other side, generators use less memory but are slightly slower than lists.

4. Can we reuse a generator?

No, once a generator is finished, it cannot be reused. If you want to use it again, then you should recreate it.

5. Where can i use a generator in real projects?

A generator can be used (in real projects) in the following scenarios:

• Reading large log files line by line

• Streaming data from paginated APIs

• Handling huge CSV/JSON datasets (processing millions of rows)

• Creating infinite sequences (like generating endless IDs, timestamps without memory limits)

• Feeding data (like images, text, logs) to models without storing everything in RAM

• Implementing ETL pipelines in data warehouses (to extract records in batches and push them downstream)

13. Summary

Everything explained in this article is based on patterns I have applied in real production systems involving APIs, data pipelines, and memory-sensitive workloads. Generators are not just a Python feature - they are a reliability tool when systems scale.

Python generators help you write scalable and memory-efficient code.

The yield statement helps you produce values one by one, which makes it a good candidate for handling large datasets, APIs, and streaming workloads.

If you already understand generator expressions, performance benchmarks, and advanced patterns like send(), yield from, and iterator integration, then you have gained the same depth of knowledge covered on websites like GeeksforGeeks and Real Python.

This is most comprehensive and practical tutorial available online and is good for the following candidates:

• Beginners or freshers

• Intermediate developers (with 2–5 years of experience)

• Production engineers

I would highly recommend you practice this important topic (rather than just reading). That would boost your confidence and knowledge. If you are preparing for backend interviews, building data pipelines, or designing memory-efficient systems, mastering generators is not optional - it is foundational.

Learn more in our “Python Tuples" chapter.