1. *args (Variable-Length Positional Arguments)

In Python, *args allows a user-defined function to accept any number of positional arguments.

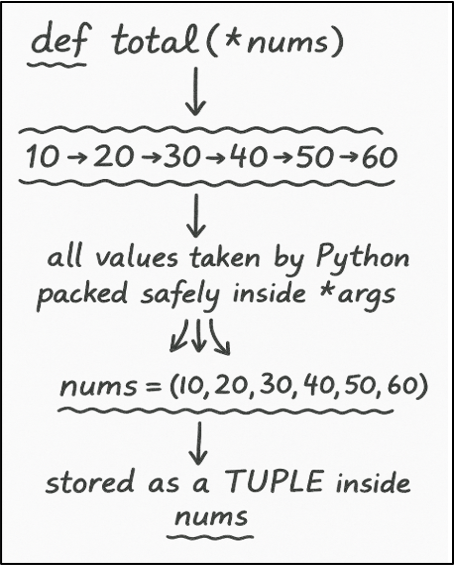

The asterisk (*) tells Python to collect all extra positional arguments and bundle them into one variable (commonly named args). Please note that args behaves like a tuple inside the function.

This is helpful in situations where you don’t know in advance how many values the user will pass. It gives your function flexibility and makes it reusable.

Syntax

def function_name(*args):

# args is a tuple containing all extra positional arguments

Example

def total(*nums):

print(sum(nums))

total(10, 20, 30)

total(10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60)

Output:

60

210

Explanation

In this example, the total () function can take any number of numbers because *nums simply gathers them together. After that, python then adds whatever positional arguments you provide and prints the final sum.

So total (10, 20, 30) gives 60, and when you pass a bigger list like 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, it prints 210.

Honestly, I like the flexibility -you write the function once, and it handles everything in a smart way.

When I first learned this, I remember testing it with random numbers just to see how Python handles them. It actually made the concept click for me.

A Simple Diagram to Understand *args:

Important Points

a) *args does not accept keyword arguments. It accepts only positional arguments.

b) *args collects all positional arguments into a tuple.

c) If you are using *args and **kwargs together, then *args should come before **kwargs.

Why It Matters

a) You can define a function that works for any number of arguments, small or large.

b) You can build clean and scalable code, especially when the number of parameters is unpredictable.

2. **kwargs (Variable-Length Keyword Arguments)

• It allows a function to accept any number of keyword or named arguments.

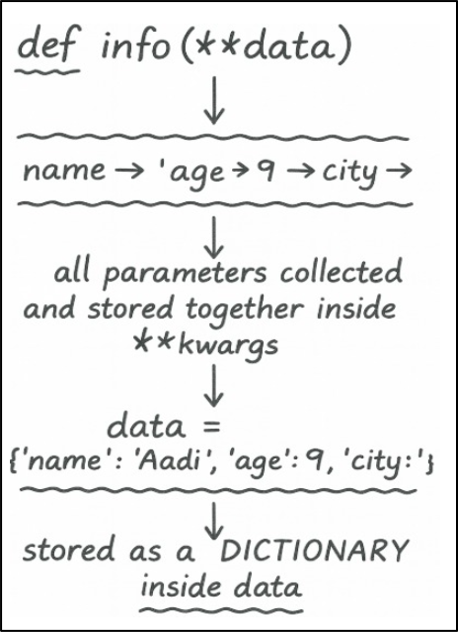

• It packs all name–value pairs into a dictionary object, where each argument name and value is stored as key–value pairs.

• It makes your function flexible, especially in situations where you have no idea how many named inputs a user may provide.

Syntax:

def function_name(**kwargs):

# kwargs is a dictionary having all keyword arguments.

Example:

def info(**data):

print(data)

info(name="Amit", age=12, city="Delhi")

Output:

{'name': 'Amit', 'age': 12, 'city': 'Delhi'}

Explanation:

In this example, the info() function collects all the named values you send to it and stores them inside a dictionary called data.

When we call the function with name="Amit", age=12, and city="Delhi", Python packs everything into that dictionary object. So, when you print, it simply gets all the details back in one place.

A Simple Diagram to Understand **kwargs:

Important Points:

a) **kwargs always collects keyword arguments into a dictionary object.

b) **kwargs does not take positional arguments.

c) In a function definition, **kwargs always comes after normal parameters and *args.

d) You can’t repeat a keyword argument; otherwise python will raise an error.

e) It is useful when parameter values are unknown, especially when you write APIs, configuration functions, etc.

f) kwargs is just a naming convention; you can use any name, like **info.

Why It Matters:

a) It makes your function more readable because name and value are written in pairs.

b) It is used heavily in frameworks and class constructors.

Difference Between *args and **kwargs

| *args | **kwargs |

| I. It takes multiple positional arguments. | I. It takes multiple keyword (name=value) arguments. |

| II. All values are stored in a tuple. | II. All key–value pairs are stored in a dictionary. |

| III. It is used in situations where number of inputs is unknown and only values are given. | III. It is used in situations where the number of inputs is unknown and names + values are given. |

| IV. In this, order of positional arguments matters because values are matched by position. | IV. In this, order of keyword (name=value) arguments doesn’t matter because names identify each value. |

| V. In a function definition, *args should always appear before **kwargs. | V. **kwargs must come after *args in the function’s parameter list, python will not accept it the other way around. |

3. Scope of Variables

In Python language, every variable that you define has a specific area where it can be accessed.

a) Local Variable

It is always defined inside a function.

Important Things to Know:

• Scope: It can only be accessed from within the function where you have defined it. You can’t use that variable outside of that function.

• Lifetime: Local variables are created only when you call that function and destroyed when execution of that function is finished.

Example:

def abc():

y = 50 # y is a local variable

print(y)

abc()

Output:

50

Explanation:

In this example, the variable y is a local variable, which means it is created inside the function and exists only while the function is running. When we call abc(), Python uses this local variable y and prints its value, which is 50.

b) Global Variables

If you define a variable outside any function, then it is called a Global Variable.

Important Things to Know:

• Scope: They can be accessed from anywhere in the program.

• Lifetime: Global variables are created from the moment they are defined and destroyed when the program terminates.

Example:

x = 10 # x is a global variable

def abc():

print(x)

abc()

Output:

10

Explanation:

In this example, x is a global variable, which means it is created outside the function and can be used anywhere in the program.

When the function abc() runs, it doesn’t create its own x, so it simply uses the global one.

That’s why the output shows 10 when the function prints it.

Modifying Global Variables:

If you want to change the value of a global variable from inside a function, then you need to declare that variable inside the function using the global keyword. If you don’t use the global keyword, Python creates a new local variable with the same name inside the function.

Example:

x = 10 # global variable

def update_value():

global x # telling Python to use the global x

x = x + 5 # modifying the same global variable

update_value()

print(x)

Output:

15

Many beginners get confused here, and honestly, I did too, until I realized Python creates a new local variable if we forget the global keyword

Why It Matters:

When your application scales in size, you have to manage multiple variables. If you don’t manage their scope properly, then even a small mistake can break your complete logic. It also helps to keep your code clean and easier to debug.

4. Lambda Function

It is a shorthand way of creating a one-line, nameless function in a quick way. It also helps to write clean code by avoiding unnecessary function definitions.

Example 1:

square = lambda a: a * a

print(square(10))

Output:

100

Explanation:

In this example, the small lambda function takes a number and multiplies it by itself to get the square.

When we pass 10, it simply does 10 × 10 (behind the scenes) and gives back 100. It’s just a short way of writing a normal function.

My advice is to use it only when your task is too small for a full function.

Example 2: Sorting a List of Tuples Using Lambda

students = [("Amit", 85), ("Ram", 80), ("Sam", 70)]

sorted_list = sorted(students, key=lambda item: item[1])

print(sorted_list)

Output:

[('Sam', 70), ('Ram', 80), ('Amit', 85)]

Explanation:

In this example, we first have a list called students where each entry is a pair containing a student’s name and their marks. In next line (second one), when we call sorted(students, key=lambda item: item[1]), Python first takes the list you gave it and then looks at the key= part to understand what it should use for sorting.

Here, the lambda tells Python, “From each student’s pair, look at the second value - the marks.”

So, Python does three things as written below:

• picks the marks from each pair,

• then compares those numbers,

• and finally, arranges the whole list using those values

5. Docstrings (Triple Quotes):

It is a small description which is written inside triple quotes.It explains what a function actually does.

With the help of a docstring, a person can quickly understand the purpose of that function without reading the complete code.

Example 1: Creating a Docstring with Triple Quotes

def add(x, y):

"""Returns the sum of two numbers."""

return x + yExplanation:

In this code, the function add(x, y) takes two numbers and returns their sum.

The line inside the triple quotes is called a docstring. It’s just a small description written inside the function to explain what the function is supposed to do. In this case, it returns the sum of two numbers.

You can also access the docstring directly using the function_name.__doc__ attribute.

Example 2: Accessing the Docstring using the .__doc__ Attribute

def add(x, y):

"""This function returns the sum of two numbers."""

return x + y

add.__doc__

Output:

'This function returns the sum of two numbers.'

6. help( ) Function

If you want to see the documentation of any function, module, or class (in Python), then you can use the help() function.

This function is useful in two specific scenarios:

• When you start learning a new module

• When you forget the purpose of a function

Example:

def add(x, y):

"""This function returns the sum of two numbers."""

return x + y

print(help(add))

Output:

Help on function add in module __main__:

add(x, y)

This function returns the sum of two numbers.

None

Explanation:

In this example, first we define a function add() and write its explanation inside triple quotes. This is called a docstring. In next line, when we call help(add), Python reads that docstring and prints the function's details on the screen.

After printing the documentation, the help() function returns None because it has nothing else to return. Since we wrapped it inside print()function, Python prints None as well. That is why you see the help text followed by the word None.

Difference between Docstring and help( )

| Feature | Docstring | help ( ) |

| What it is | It is a short explanation written inside the function. | It is a built-in function that shows the function’s explanation. |

| Purpose | It describes what the function does. | It reads and display the docstring to the user. |

| Where it is used | You write it Inside the function definition using triple quotes. | You call the it using help (function_name) by calling it. |

| Who uses it | It is written by the programmer who writes the function. | It is used by anyone who wants to understand or explore how the function works. |

Learn more about Functions in our “Advanced Python Functions" chapter.